This blog series was written jointly with Amine Besson, Principal Cyber Engineer, Behemoth CyberDefence and one more anonymous collaborator.

This post is our first installment in the “Threats into Detections — The DNA of Detection Engineering” series, where we explore opportunities and shortcomings in the brand new world of Detection Engineering.

Detection Engineering Defined

As many of you already know, detection engineering is the process of building, refining and managing detection content (rules, content, code, logic — whichever word is most suitable for you). It is a relatively new discipline, but it is rapidly gaining importance as the threat landscape becomes increasingly complex and (for top-tier threat actors) more targeted to each environment.

It rewrites the classic SOC-building handbook by putting an emphasis on detection quality from the start, and dedicates capacity directly to the content engineering concern (as we say multiple times in our Autonomic Security Operations materials). Detection engineers also work closely with other security teams, such as threat intelligence and incident response, to ensure that their detections are developed quickly and work well.

It is a challenging field that requires a deep understanding of both security and software engineering. On the security side, detection engineers need to be able to identify and understand the latest threats and attack techniques. They also need to be able to develop and maintain detection rules and signatures that can accurately identify these threats. On the software engineering side, detection engineers need to be able to develop and maintain detection systems that are scalable, reliable, and efficient. They also need to be able to tune and optimize these systems to reduce false positives and negatives.

There are many broad challenges that detection engineers face, including:

- Messy threat landscape: The tactics and tools that attackers use are constantly changing, making it difficult to keep up with the threats. Understanding attack chains performed by threat actors is complex work that needs to be performed both quickly and reliably (false negatives and/or false positives can ruin the program). Naturally, attackers also have an interest in not being detected, at least in some cases.

- The need for speed: Detection systems need to be able to identify threats quickly in order to minimize the damage they cause — new detection content needs to be rolled out ASAP once threat intelligence is received. All this should work in the context of increasing volumes of telemetry data, without incurring the engineer burnout.

- The complexity of data and systems: Detection systems need to be able to process large amounts of data from a variety of sources, including network traffic, cloud services and endpoint data. When logs are not parsed properly, or doesn’t contain required data, detections lean on the poorer side: garbage in, garbage out. Reliable and fast detection engineering for IT “layer cake” from mainframes to containers, present in many environments, is not getting easier. The age of “I just need to know a few popular Windows event IDs to detect” is long over.

With capable threat actors mastering both LOL and custom malware, and with the realization that a lean, reproducible, and efficient workflow is required to go from threat to detections, we have seen more signs of the evolution from generic security analysts who operate on canned or lightly tuned detection content to more dedicated roles like threat hunters and detection engineers. We are also seeing further signs of the common L1/L2/L3 concept progressively dissolving, which moves the role of the detection engineer to the front of the detection battle.

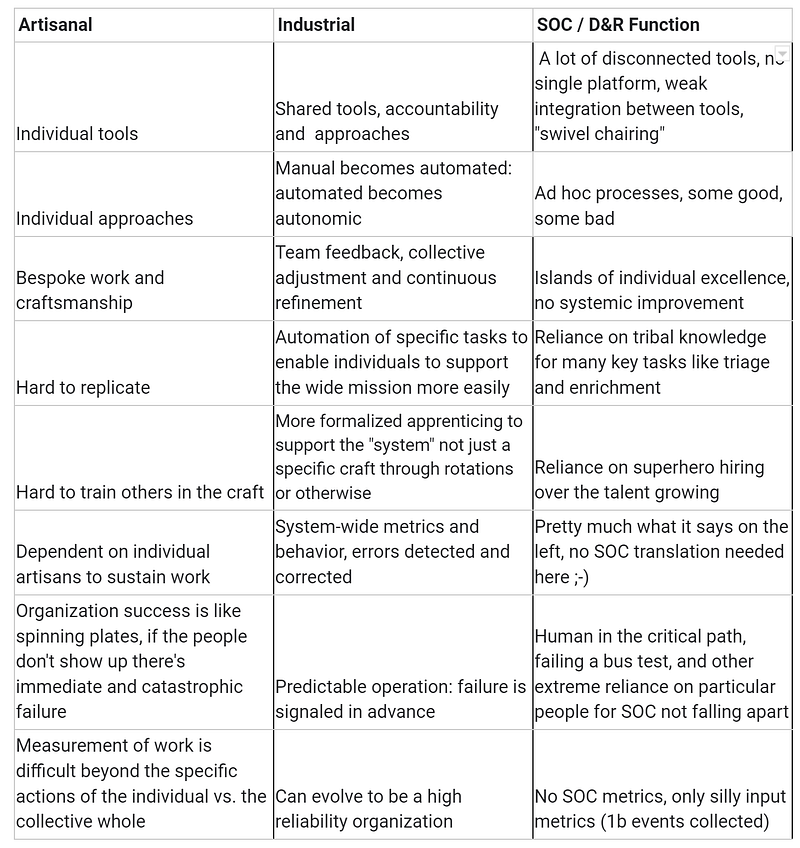

Things As They Stand

At many companies, Detection Engineers started to be differentiated as a separate role 2–3 years ago (and, yes, we have seen organizations that had similar roles for a decade or more), and while they’re now in demand, they are still somewhat of a rare breed.

In some organizations, an L3 analyst tends to be designated to do the same activities as detection engineers, but also have the double (triple if they also hunt) duty to perform investigations, or hunt threats without always plugging into new detections. This is less optimized than having a fully dedicated capacity, but is indicative of the push toward conscious detection content development (it is perhaps better for an overburdened L3 to do this compared to … nobody, at least as a transition stage)

On the other hand, threat intelligence teams (outside of SOC) have had a hard time scaling to detection engineering needs. This leaves detection engineers often having to do the bulk of the threat research required to build detection backlog items and often even having to select intelligence sources themselves. Ideally, this process would be collaborative, to allow a continuous and smooth handover of actionable CTI data to detection engineering teams.

In the next part, we will cover scaling the intelligence to detection content pipeline.

UPDATE: the story continues in “Detection Engineering and SOC Scalability Challenges (Part 2)”

Related blogs: